inner boy healing

softly embracing my transmasc femme non-binary genderfluid snowflake energy ❄️

There is no such thing as a ‘real man’.

— JJ Bola, Mask Off: Masculinity Redefined

“What is masculinity?” is a really existential question for me as a transmasculine person. I didn’t anticipate that wanting to write about masculinity as part of my own healing journey would feel so overwhelming, but damn, it’s tough. I was spiralling.

I was questioning my whole approach.

Maybe I need to intellectualize less.

Feel more instead. Write poems only.

Just for context of what I’m navigating too:

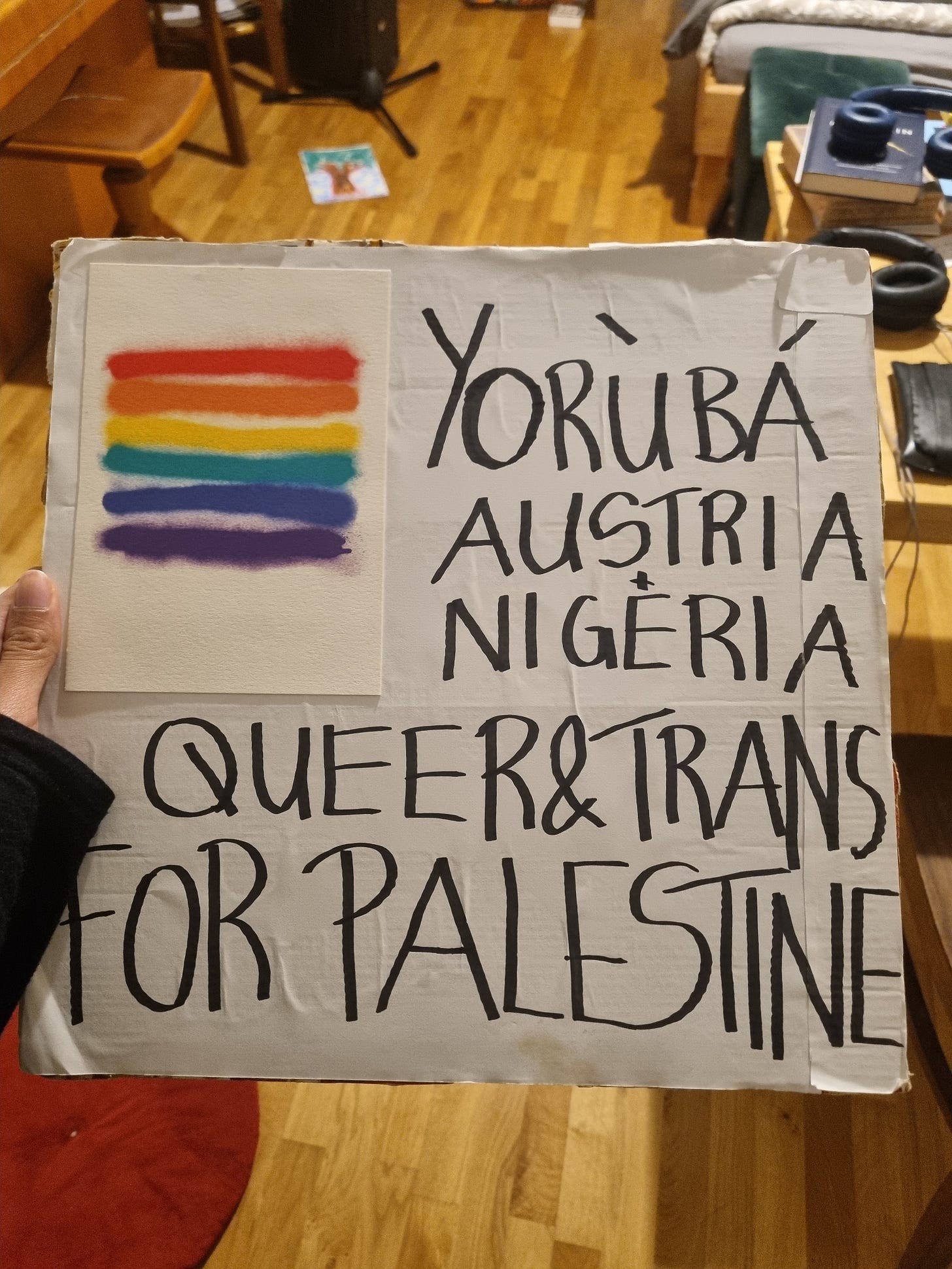

We’re experiencing transphobic legislative backlash in Austria. It might be that the rights for trans people to have our chosen name and gender identity reflected on legal documents are revoked. From the media, that’s what we’re hearing. However, from a local LGBTQ+ organization, I’ve also heard a different story: That binary trans people are still going to be able to transition and it only affects non-binary trans people.

It’s interesting that even though the struggles of non-binary people get dismissed very easily, even within trans spaces and even though we are called snowflakes a lot: Look at how scared those in power are of us? I could feel the fearmongering of “Kamala is for they/them, President Trump is for you” all the way across the ocean. *big sigh*

I’m feeling a lot of emotions all at once.

A part of me is still dissociating.

This can’t really be real, can it?

The other part of me isn’t surprised and finds the timing of this decision in tandem with Trump’s inauguration very suspicious, but apt. The West is showing its face. Taking the mask off. However, not in a way that leads to more vulnerability and care. The care for queer and trans rights has been conditional on being able to pinkwash their colonial projects. See: Israel. Since they’ve been able to carry out their imperial agenda, mostly with impunity and even ardent support, they don’t need to protect us as an alibi anymore. They no longer have a need to pretend that they are somehow superior to the people they are colonizing by being ‘the most gay and trans-friendly’. Most major trans organizations in Austria, who are also majoritarily white, chose to align with the Israeli state and stay ‘neutral’. They chose to silence Palestinian solidarity and voices. To say I was disappointed is an understatement. Protesting as queer people of color for Palestine on the streets of Vienna means harrassment.

Now, I cannot help but feel numbness. It’s a similar feeling as with seeing celebrity houses burn down in the LA fires. It’s not that I don’t care. It’s just that the fires have been burning in Congo, Sudan, Palestine and other places for decades, if not centuries. They chose to remain silent and ‘neutral’. The power they had, they didn’t use it responsibly, but only for their own safety and wealth accumulation.

Being trans in itself isn’t radical.

Being gay in itself isn’t radical.

Being queer in itself isn’t radical.

Being an artist in itself isn’t radical.

It just has the potential to be.

None of the great icons we consider radicals strove to be radical, they strove to be upright and conduct their lives with as much integrity as possible.

— Minna Salami

However, marginalized groups also don’t need to be radical to deserve support. Even though I’m disappointed by the lack of solidarity by those trans organizations who had and still have the most power to shape public discourse in Austria, I of course support the rights of trans people. I’m one of them, after all, and also affected by this law. I was told they remained silent to not lose funding and for strategic reasons, but did it help? No, it didn’t. White supremacy — so, the pathologization of anything and anyone not white-cis-het-male — and transphobia go hand in hand. Nazis and Zionists have never cared about the rights of trans people. The don’t care about reproductive rights and even less gender affirming care. Let’s not delude ourselves! Austria, please stop with the delusion that supporting Israel can be a leftist stance!

Now: Back to the question of masculinity. However, reflecting on how resistance is viewed and movements for liberation are organized has more to do with gender than we might assume on the surface level. The idealization of armed struggle often brings with it its own messy bag of toxic masculinity. Women fighters are easily glorified too, which has led to a case where people shared the image of a female Israeli solider, celebrating her, because they’ve confused her for a Palestinian resistance fighter.

I cannot find the image right now, but maybe you know which one I mean.

I’ve been listening to “Emergent Strategy” by adrienne maree brown and this passage also sparked some deeper reflections on the role of masculinity in movements:

“I was the executive director of The Ruckus Society for four and a half years, starting in 2006. Ruckus has historically been the kind of organization that wouldn’t be described as feminist. Founded in 1996 on the model of Green- peace action camps—get a hundred activists in the woods and show them how to do non-violent civil disobedience in an effective way— Ruckus was rooted in a masculine action culture.

The best way I can explain this culture is penetrative. Rather than forming long-term partnerships with communities, Ruckus was in and out with mind-blowing, creative actions. This was in line with a model of action grounded in spectacle. The politics were radical and the actions historic, but there wasn’t a sense of community ownership or engagement in the work—which meant that at a fundamental level the power dynamic wasn’t changing. The communities still come to rely on someone else to change their situation.

Over years of amazing work, coupled with critiques about the approach, Ruckus went through what could perhaps be called labor pains to bring forth the model and structure we currently have—which includes a team of women, majority queer, at the staff level. The frustrations folks had with Ruckus are very much the frustrations alive in our movements right now—we had a vision for the kind of world we wanted to see, but we weren’t modeling that internally. We wanted strong local economies where communities felt responsible for their neighbors’ well being, but Ruckus wasn’t actually developing local direct action know-how.

Out of this moment in our history, a new program was born that trans- formed how we worked. It was called the Indigenous People’s Power Project (IP3). The model was to build a body of Indigenous organizers who became action experts within their own communities. In the process of getting this project off the ground, Ruckus was challenged to grow into something we couldn’t even have imagined.”

This story shows why considering patriarchal power dynamics matters in social justice movements, but I struggle with penetration as a metaphor for masculinity.

Is this truly the only way masculinity can be viewed?

Is that truly what defines masculinity?

One of the challenges is how to acknowledge the dominant narratives around masculinity and femininity without reinforcing clichéd ways of viewing gender.

I’ve learned that I can never give people a satisfying answer for why I’m trans. If I tell them about my experiences of craving to wear trousers as a child and feeling like a part of my identity got stripped away, when I was forced to only wear dresses and skirts from the age of five, people are going to tell me: “But can’t women wear trousers too?!?!?!” Yes, absolutely. That’s just one way gender dysphoria showed up for me. Just because cis women share my experiences doesn’t make them all trans, but it doesn’t make me cis either. We can have the same lived experiences, but a different identity. When I say that my masculinity feels gay, people can say to that: “But aren’t YOU creating stereotypes about gay men?!?!?!” It’s true that there are all kinds of hypermasc, gay men. Straight men wear makeup and do ‘feminine’ activities too. When I say I’m gay, I’m talking more about my desire for men, which doesn’t come from a place of desiring them as a woman, but as a man myself. Hard to explain. That again doesn’t have to mean anything specific when it comes to sexual activities. I do have my dsyphoria here and there with certain sexual fantasies and expectations, but I am also able to deconstruct them so it then again doesn’t really matter anymore. You would have to actually be in my body to understand my transness. Nobody is expecting people who have never given birth to be able to fully relate to that either.

This is one of the many experiences that I had growing up that made me question my masculinity, leading me to reflect on the question that we’re not supposed to ask: what does it actually mean to be a man? Why was it that in one part of the world, two men holding hands did not turn any heads, yet in another part of the world everybody stopped and stared? I wondered about men’s emotions and feelings, or rather, the apparent absence of it.

I was quite an emotional boy. I cried if I was sad or upset; I cried if I was happy; I cried from anger. I expressed myself fully. But as I got older, this slowly changed. I become more stoical, more repressed, more reserved; I never let anyone else know how I truly felt, sometimes not even myself. There was a burning anger or rage inside that I disguised as anger issues, a short fuse or inability to control my temper.

Moving forward to the present day, what do our own perceptions of masculinity and the wider cultural norms around it mean for young boys growing up into manhood? What do they mean for young men and older men grappling with a society that encourages them to hold on to the anger that destroys the lives of women as well as the lives of many men? There are many urgent questions to consider about modern-day men and masculinity. Why are men overwhelmingly represented as perpetrators of violent crimes in statistics, particularly in regards to sexual violence, from harassment to rape? Why is suicide the biggest killer of men under the age of 45 – more than disease or accidents? What can we do to change this?

— JJ Bola, Mask Off: Masculinity Redefined

I want to explore this question in this month’s Inner Poet Calling group session today. However, nobody has signed-up yet and I also have had a lot going on in my life that has made it hard for me to truly spread the word and prepare myself for it. I do write because I care about change, but at the end of the day, I’m also doing it for myself. I’m choosing the themes of my sessions based on what I also feel a need for liberation around. Masculinity is a very tender topic for me. Listening to JJ Bola, I’ve been crying a lot for my inner boy and wondering if inner boy healing is something everyone needs, not just men. If we all can have inner mother and father figures, why shouldn’t we also all have inner boys and girls? What my inner boy needs is different from what my inner girl needs? That is not because boyhood and girlhood are essentially different but because there are different conditions around them. I don’t want to fall into the trap of essentializing gender roles. Yet, pretending those differences aren’t there isn’t helpful in the healing process. I would say in order to heal it is important to first acknowledge how things truly are, without sugarcoating, in order to then be able to break free from the status quo. Jumping over the validation and acknowledgment part feels like toxic positivity and suppression. We have to acknowledge the gender binary in order to truly live non-binary lives.

Love,

Imọlẹ

PS: Please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. It means a lot. 🌧️

PPS: If you can, use Ecosia, instead of Google. I do too. For the Congo! ❣